A Retrospective Assessment

The Brisbane Solidarity Network was a somewhat large and influential anarchist collective that existed roughly between 2008 and 2015. It involved a diverse range of people and had both its successes and failures. While the organisation did eventually collapse, it is worth remembering BSN primarily because it was so important in reinvigorating the anarchist movement in Brisbane, which although had not been dormant since the disintegration of the Self-Management Group decades prior, had lacked a group with a truly organisational perspective.

BSN could trace its origins to 2006, when a group began to coalesce around the politically conscious Brisbane punk scene. Initially named the Direct Action Collective, a project that folded swiftly, the idea started to take shape in the form of the Ipswich/Brisbane Community Action Trajectory in 2008. From the outset, we saw the group as having a very specific role, concerning itself more with confronting directly with issues facing poor people, such as homelessness and welfare cuts, than engaging with what we perceived as leftist ghetto organising. Through this sort of organising, we planned to assert a dual-power strategy, winning people to anarchism by demonstrating the benefits of community-led organisation over state-based solutions.

Almost immediately, the project began evolving, becoming the Brisbane Solidarity and Mutual-Aid Network (BSMN) by the years end. By February ’10, we hosted an event to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the Spanish Revolution and put together a magazine called Wildcat, reflecting our identification with anarcho-syndicalism. The group took a strong interest in contemporary issues, particularly welfare quarantining. From the outset we wanted to realistically confront what was important to poor people and the mantra throughout the group’s existence remained consistent- “is it winnable?” In January 2011, the name was permanently established as BSN. The group started to make some real progress, talking with boarding house tenants in particular and confronting corrupt landlords. One of the real triumphs of BSN, however, was the large-scale publishing of the Crisis Manual, a resource for homeless people which was distributed in massive numbers, reaching such a level of popularity that it was co-opted by the Brisbane City Council, which republished it with the sections on squatting and anarchism omitted.

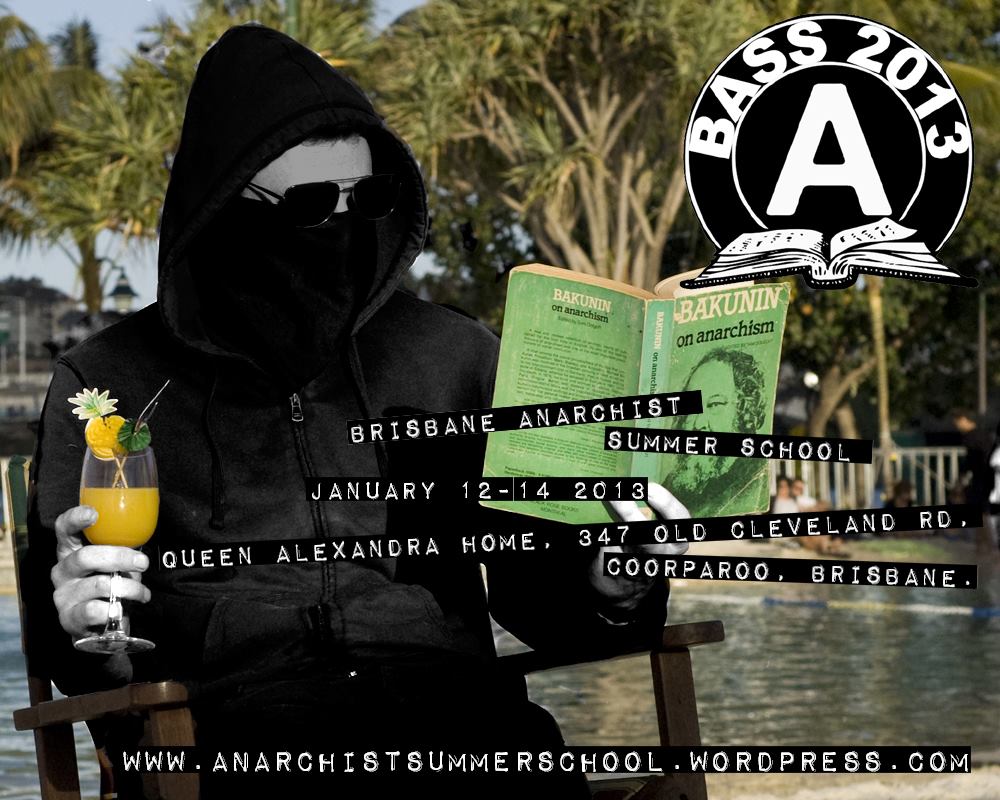

The organisation also did a great deal of international solidarity work, but this is perhaps where BSN began to lose its focus on community organising. In 2010 we formed a strong relationship with Etniko Bandido in Manila. When Cyclone Haiyan devastated Tacloban City in 2013, for example, BSN supported the Manila anarchists in their relief efforts, however modestly. BSN would continue to work with anarchists abroad sporadically, including funds raised for an anarcho-queer space in Yogyakarta and medical expenses for Nigerian anarchist leader Sam M’Bah, who unfortunately did not survive heart surgery. We attracted a fair number of foreign anarchists to our ranks, from Norway, France, South Korea, Italy and England, among others, giving us a feeling of connectedness to groups abroad. We also began to foster strong relationships with similar groups around Australia, such as the Black Swan collective in Adelaide, Jura Books, the IWW and the ASF, and cautiously involved ourselves with efforts to bring about a federation that never materialised. Around this time we participated in bringing about the Brisbane Anarchist Summer School in conjunction with Black Current Anarchist Distro. BASS was successful in bringing together perhaps 300 anarchists and at the time built towards a sense of integration in the Australian movement.

The project continued on for some period with limited success, perhaps the most successful being the organisation of a front including the CFMEU to rout Golden Dawn neonazis from Musgrave Park in 2014. The group started to fall apart around the same time as the protests against the G20 Leaders Summit later that year, however. The focus on tenant’s rights had by this point been largely lost and BSN was more-or-less participating in issue-of-the-day politics and various individual projects. The real rot set in when working groups were given the group’s blessing to essentially act as if they were independent of the central body. Some people wanted to concentrate on prison abolition while others focused on forming a sound art collective. Some wanted to take it down a more militant trajectory, which led to the formation of the Brisbane Anarchist Direct Action Solidarity (BADAS) group, while during the G20 Leaders Summit the main part of BSN committed its resources to backing the newly formed Brisbane Street Medic Collective. On the day of the Summit the leader of the BADAS group, who went on to embrace Maoism, was arrested at Roma Street train station after setting out on her own in black bloc gear carrying a knife and a BSN banner, opening up the possibility of police raids against other members similar to those faced by the Melbourne movement after the 2006 G20 riots. The splintering of the group into special interest groups and the turmoil this caused us financially, not to mention personality clashes and something of a drinking culture, essentially caused the organisation’s demise. There were attempts to revive it, one of which at the Stone’s Corner Hotel attracted somewhere in the vicinity of 30 experienced activists, but the energy was simply gone.

The organisation never formally disbanded but members floated off and engaged in other projects, including the IWW, the Running Wild Collective, Rojava Solidarity Brisbane, SE QLD Social Ecology, Dorothy Day House and Turnstile, Antifascist Action, the Anarchist Black Cross and Unite. By 2016 the organisation could safely be said to have finally vanished, its final event being a solidarity night for Jock Palfreeman and the Bulgarian Prisoners Association. Unite would prove to be the main torchbearer to continue BSN’s experience, both in positive and negative ways. Formed after an internal rebellion in the Socialist Alliance, in which a libertarian socialist faction seized control of the organisation’s Brisbane premises, Unite too was a broad coalition of people from different tendencies, this time including anarchists, autonomists and social-democrats. Unlike BSN, however, the anarchist tendency did not disintegrate and instead left Unite once its ideological incoherence began to threaten the survival of the movement. This group retained control of the space, which is now called Common House.

The primary problem BSN had from the outset was the gap in generational knowledge and experience. With the exception of some independent projects, such as Brisbane Anarchists Sabotaging the Australian Representative Democracy (BASTARD) and the Black and Green Infoshop, there was a sustained gap in large-scale anarchist organising in Brisbane, dating back to the demise of the Self-Management Group. While BSN was in contact with SMG veterans, few of them were willing to talk about their experiences in that group and whatever documents we could find from that period we found largely impenetrable, grounded as they were in the politics of the time. We were therefore more-or-less forced to work things out as we went along with barely any experience and with almost every member having a different vision for what they wanted from the group.

Our open-door policy frequently led to catastrophe, as people with wildly different political approaches, levels of emotional maturity and grasp of concepts such as sexism and homophobia were swept into the group. It also meant that we constituted an unworkable coalition of political stances. Anarchists of communist, syndicalist and individualist persuasions found themselves working together without any real structure, uniting principle or goal beyond an affiliation with anarchism. By contrast, it is my belief that the group could have benefited from a study of the platformist and especifist traditions. Platformism is an organisational strategy developed by Dielo Truda, a network of Ukrainian and Russian anarchists that formed in Paris after the defeat of the Makhnovist movement. Its fundamental belief is that an anarchist organisation’s members should be in congruence around key themes, namely tactical and theoretical questions and collective responsibility. If an organisation is to be successful, it is a prerequisite that its members should agree with the theoretical and strategic orientation of the group. While this may seem obvious, it has been a source of contention throughout anarchism’s existence.

Responding to Fraure’s 1927 defence of synthesism, the belief that the various tendencies of anarchism can coexist within the same organisational framework, Delo Truda noted that these tendencies either “remain independent tendencies, in which case how are they going to prosecute their activities in some common organisation, the very purpose of which is precisely to attune anarchists’ activities to a specific agreement? Or these tendencies should lose their distinguishing features and, by amalgamating, give rise to a new tendency that will be neither communist, syndicalist or individualist … But in that case what are the fundamental positions and features to be?” They went on to note that “the notion of synthesis is founded on a total aberration, a shoddy grasp of the basics of the three tendencies, which the supporters of synthesis seek to amalgamate into one.” This argument is redeemed by the experience of BSN, which in trying to bring together disparate approaches to anarchism was never really able to gain any real theoretical or strategic approach. The fact that not one attempt was made by the organisation throughout its existence to discuss some of anarchism’s key texts speaks volumes to the fact that it in fact had an underlying fear of theory on the basis that any attempt to grapple with it could cause friction. While we can celebrate difference in the anarchist movement, it is my view that Delo Truda was correct in arguing for groups that are internally coherent.

BSN’s existence was chequered. It was a collection of remarkable personalities and it had its share of victories and defeats. The fundamental problems with BSN were with its failure to vet new members and bring them up to a reasonable level of political education, its refusal to engage with theory, its avoidance to building up any real strategic approach and its lack of internal discipline and collective responsibility. For these reasons, there is no need to mourn its passing. We can instead celebrate BSN as a step forward in the advance of Australian anarchism, one that was fatally flawed but allows us to look ahead with greater clarity. Experimentation is necessary in a movement that seeks to topple a system as dynamic as capitalism and it is through these sometimes painful lessons that anarchists can build stronger and more resilient structures capable of furthering the revolutionary project.